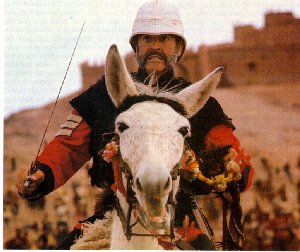

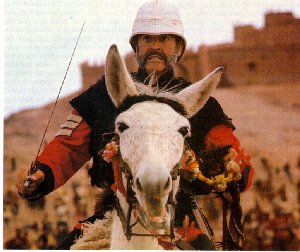

From James Bond in 'Dr. No' to prisoner John Mason in 'The Rock', Sean Connery's carreer has favoured clever rogues and learned rebels.

Thirty-five years ago, Honey Ryder walked out of a tropical ocean to sing 'Underneath Banana Tree'. On the beach beneath a tree slept a handsome man, dressed in the blue of the sea, his hair and eyebrows so dark they were called "black Irish". He was 32 years old - and Dr. No was about to make him one of the biggest stars of the post-studio era. He woke to the sound of singing: the sight of Honey (Ursula Andress), blonde in a blonde bikini, a Botticelli Venus rising from the waves, brought curiosity to his face, then desire, then the hint of a cocky plan of seduction.

The man, of course, was Sean Connery as james Bond, a working-class Scot playing an upper-class product of the English establishment. Bond seemed sexually and sensually free in an archetypically 60s way, yet he came from a pre-60s world, in which Britain was still a mighty colonial power. "Mr Kiss Kiss Bang Bang", as Italians knew him, had the arrogant Empire-born assumption that the world was his oyster: men wanted to be him, women wanted to bed him. He was the creation of a writer formed by Eton, Sandhurst and the British Secret Service: lan Fleming. Connery's youth could not have been less like Fleming's, but he learned about the Windsor knot, buttonless cuffs, sporty cars and chemin de fer from Fleming, from Dr. No's director Terence Young, and from his unlikely new friend Noël Coward. They had him shave his eyebrows, bought him hand-made shoes (the overall Dr. No budget wasn't huge, but the clothes costs were), and sent him to elocution lessons.

But this wasn't just an upper-class make-over, rendering a promising lower-orders oik properly clubbable. Connery, already in love with the idea of learning, was a more-than-willing candidate, yet his sense of justice and morality was so well formed by 1962 that his blue-blood mentors hadn't the remotest chance of remaking it in their own image. Those who Conneiy grew up knowing and loving earned little and enjoyed no privileges, which made him an instinctive rebel - except that he also keenly wanted to escape the constraints of such an upbringing. Once he began acting, he was mixing with people far more politicised than he (he dated Michael Foot's daughter julie), and becoming aware that some get on because they are born posh. He also began to understand the politics of Scotland's relationship with England, all of which make his casting as Bond, the Empire mentality in a Saville Row suit, seem distinctly incongruous (no surprise Connery considers Fleming "a terrible snob"). But one of the more utopian aspects of 007's world is the near-total absence of authority figures: there's only M, that utter stay-at-home; once on a mission, Bond took orders from no one. Certainly if this is the key to Connery's take on Fleming's character, the same ambivalent combination - of rebellion with respect for the need to widen horizons - is what gave tension and coherence to his movie career.

The key event in Connery's late teens, which he still talks about, was a three-year spell in the Royal Navy. He joined the Sea Cadets in 1946 at the age of 16, then the RN for a planned seven- year stint. But after three, he was out. He hated military life, internalising his frustrations until invalided by duodenal ulcers. His problem, as he tells it today, was with unquestioning compliance. Bright enough to see the officers weren't always right, he realised that an absolute system of command was the militaiy's secret of success. You can argue against a bad order after the fact, but only, as he says, if you're alive to do so.

Almost every good Connery film reflects the emotional-intellectual dilemma he confronted in those Navy days: the nature of authority and how to challenge it. One of his first decisive career moves, only a year or so after Dr. No, was to re-negotiate his contract with the Bond producers, Broccoli and Saltzman. And his on-screen conviction comes from that same acid in the gut.