In Sidney Lumet's The Hill (1965)  - entirely about how the military

crushes individualism - Connery plays joe Roberts, imprisoned by his

own army in North Africa for disobeying orders. The hill of the title

is a vicious punishment climb that offending soldiers are marched up

and down, to break their will. The Hill could not be a clearer attack

on the absurdity of military rule. The climbing is nothing but the

means by which superiors maintain their superiority, an instru-ment

of otherwise pointless power. As Roberts, Connery rages against this

power, fighting back, mocking a sergeant major's command. He's "no

tin-pot soldier", he yells: the orders are "stupid and out of date"

and "there are too many people in this army giving orders". He's

enraged, out of control, falling around, slavering. "It's what I

would have written," he told me.

- entirely about how the military

crushes individualism - Connery plays joe Roberts, imprisoned by his

own army in North Africa for disobeying orders. The hill of the title

is a vicious punishment climb that offending soldiers are marched up

and down, to break their will. The Hill could not be a clearer attack

on the absurdity of military rule. The climbing is nothing but the

means by which superiors maintain their superiority, an instru-ment

of otherwise pointless power. As Roberts, Connery rages against this

power, fighting back, mocking a sergeant major's command. He's "no

tin-pot soldier", he yells: the orders are "stupid and out of date"

and "there are too many people in this army giving orders". He's

enraged, out of control, falling around, slavering. "It's what I

would have written," he told me.

The style of The Hill is as rebellious as its content: no girls,

locations, colour, music, post-synching (some US prints were

subtitled) or stand-ins - Lumet and Connery rejecting the fantasy

world of the Bonds in favour of aesthetic rigour. Long takes followed

the actors themselves up and down the hill in brutal midday heat.

Much was shot against the light.

The Rock (1996), though flawed - it sets up a fascinatingly

complex mythic-moral world, then dumps it half way through - is The

Hill for the video age. Both portray places of correction, looming

man-made symbols of the law. In the later film, Ed Harris is the

leader of a bunch of rebel marines, rightly outraged at the way the

US government misleads or ignores the relatives of those killed in

service. To force a change in government attitude, they take hostage

a group of tourists visiting the now-decommissioned Alcatraz - the

'Rock', as it's known. Connery is John Mason, a British national

jailed for "longer than Mandela", and the only man who ever escaped

from the Rock. His knowledge is needed to defeat Harris' scheme. As

in The Hill, the law (this time the US government) is wrong, the

world mad, the Holy Grail in the hands of fools. Mason, a Roberts 30

years on, has as little respect as his younger counterpart for the

abstract rulings of the pow-erful - but he has also given up hope of

the possibility of change, directing his energies towards internal

transformation.

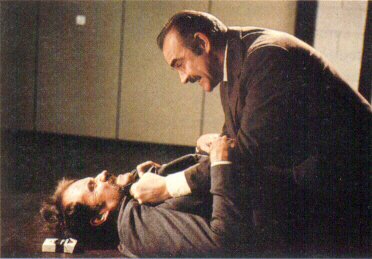

Connery's second

Lumet picture (of five altogether) was The Offence (1973), made only

because Connery insisted in his Diamods Are Forever contract with

United Artists that they fund two other films of his choice (the

second was never made). Connery plays Detective Sergeant johnson,

ajaded lawman who kills a suspected paedophile. In long takes and

wide/close montages, johnson reveals a Marnie-like secret: he too has

paedophiliac feelings. This time the law is right - and Connery's

character's moral imperative is not to challenge it but to admit to

his profound inability to live up to its demands.

Connery's second

Lumet picture (of five altogether) was The Offence (1973), made only

because Connery insisted in his Diamods Are Forever contract with

United Artists that they fund two other films of his choice (the

second was never made). Connery plays Detective Sergeant johnson,

ajaded lawman who kills a suspected paedophile. In long takes and

wide/close montages, johnson reveals a Marnie-like secret: he too has

paedophiliac feelings. This time the law is right - and Connery's

character's moral imperative is not to challenge it but to admit to

his profound inability to live up to its demands.

Yet the film's unflinching exposure of how authority is open to

corruption by weak men makes it as oppositional a work as the first

Lumet picture.

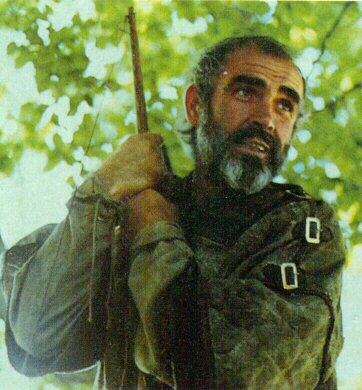

No Connery picture better exemplifies the actor's attitudes

towards authority than The Man Who Would Be King (1975). John Huston

- who thought the late scenes in The Offence among the best

film-making he'd ever seen - had long wanted to make a movie of

Kipling's novella about two ex-army rogues (Connery's Danny; Michael

Caine's Peachy) mistaken for Great Men by the tribespeople of

Kafiristan. Gently gorgeous in several ways, the film is a massive

Ealing com-edy, a mythic Dad's Anny, about Freemasonry, the farce of

succession and the birth of tolerance (the pan-and-scan video

currently on sale in the UK is a desecration, but there are plans for

a theatrical release in 70mm this summer).

Two scenes are relevant here. In the first, drip-ping with irony

and played for laughs, Connery teaches the locals to "stand up and

slaughter your enemies like civilised men" and insists that, in an

army, you "must not think". With precisely the same subject as the

"tin-pot" scene in The Hill, it comments deliciously on the Bond

series and is deeply anti-military.

The second may be the best scene in Connery's career. By a fluke,

he is crowned King of Kafiristan. In his first courtly encounter with

his subjects, he is asked to adjudicate on a dispute: a peasant asks

permission to raid a neighbouring village. He refuses

consent,announcing instead a new co-operative system: a proportion of

each village's annual harvest will be stored centrally, to help those

whose crops fail. As an actor, this is Connery's primal scene. Here

he is, making the law. All the lawmen he plays elsewhere, all those

guys who challenged authority because it had been corrupted, are

downstream of this moment, living in worlds struggling to remember

what the law - made earlier, by others - is for.

But the scene is more resonant still. In a film that criticises

the English way fiercely (Connery the Scottish Nationalist surely got

some kick out of playing it), it quietly rages against Freema-sonry,

inherited privilege and (especially) the cor-ruption of power. The

interloper king's ruling could so easily have been a feudal or

fascist one. But the final irony of The Man Who Would Be King is that

the undeserving wielder of power wields it wisely - and even so the

system is still wrong.

Unhappy with his earnings, Connery then sued the distributor,

Allied Artists, with such success it went bankrupt. In fact, he has

sued almost every Hollywood studio, which suggests that he sees them

as a movie-world establishment, a cinematic officer class. There's a

Robin Hoodness to this - the proceeds even sometimes go to charity -

that must surely help endear him to the public (he played Hood in

Robin and Marian, 1976).

Raymond Williams has written on the problems of communication and

identity which arise when working-class people move from bookless,

powerless worlds into book-filled, powerful ones. Perhaps Connery's

first contacts with the very well read left him feeling out of his

depth, but his love of books is clearly more than a cultural

keeping-up-with-the-joneses or it would have faded as soon as he made

it big. Instead, the acquiring of knowledge becomes an increasingly

important theme in his films.

He left Darroch Secondary School, Edinburgh, in 1943, at just 13.

Though bright, he hadn't read much. In 1954, as a beefy member of the

chorus in the stage musical South Pacific in Manchester, he was asked

by fellow Scot Matt Busby, manager at Manchester United football

club, to join the team. Connery asked friends what he should do.

Robert Henderson, an American actor in the cast, advised him that a

soccer career would be over in ten years, but you can act until the

end of your days. The part in South Pacific had been no more than a

fun spin-off of bodybuilding (he got it via a Mr Universe

competition), and Connery had not then considered the stage as a

career. But Henderson went on to say something that seems to have

captured Connery's imagination: "To be an actor you need to be able

to look like a miner, and to have read Proust."

This he did, within the year (though he wouldn't get to play a

miner until 1970, in Marry Ritt's under-valued The Molly Maguires,

Connery's biggest commercial flop). By the late 50s, he was already

beyond mere beefcake, onstage and in television: he appeared in

Eugene O'Neill's Anna Christie; played Proctor, the lead in Arthur

Miller's The Crucible; and Hotspur in a 1 5-hour BBC series based on

Shakespeare's historical plays.

PART 3

copyright: Sight and sound magazine, taken

from the may '97 issue

- entirely about how the military

crushes individualism - Connery plays joe Roberts, imprisoned by his

own army in North Africa for disobeying orders. The hill of the title

is a vicious punishment climb that offending soldiers are marched up

and down, to break their will. The Hill could not be a clearer attack

on the absurdity of military rule. The climbing is nothing but the

means by which superiors maintain their superiority, an instru-ment

of otherwise pointless power. As Roberts, Connery rages against this

power, fighting back, mocking a sergeant major's command. He's "no

tin-pot soldier", he yells: the orders are "stupid and out of date"

and "there are too many people in this army giving orders". He's

enraged, out of control, falling around, slavering. "It's what I

would have written," he told me.

- entirely about how the military

crushes individualism - Connery plays joe Roberts, imprisoned by his

own army in North Africa for disobeying orders. The hill of the title

is a vicious punishment climb that offending soldiers are marched up

and down, to break their will. The Hill could not be a clearer attack

on the absurdity of military rule. The climbing is nothing but the

means by which superiors maintain their superiority, an instru-ment

of otherwise pointless power. As Roberts, Connery rages against this

power, fighting back, mocking a sergeant major's command. He's "no

tin-pot soldier", he yells: the orders are "stupid and out of date"

and "there are too many people in this army giving orders". He's

enraged, out of control, falling around, slavering. "It's what I

would have written," he told me. Connery's second

Lumet picture (of five altogether) was The Offence (1973), made only

because Connery insisted in his Diamods Are Forever contract with

United Artists that they fund two other films of his choice (the

second was never made). Connery plays Detective Sergeant johnson,

ajaded lawman who kills a suspected paedophile. In long takes and

wide/close montages, johnson reveals a Marnie-like secret: he too has

paedophiliac feelings. This time the law is right - and Connery's

character's moral imperative is not to challenge it but to admit to

his profound inability to live up to its demands.

Connery's second

Lumet picture (of five altogether) was The Offence (1973), made only

because Connery insisted in his Diamods Are Forever contract with

United Artists that they fund two other films of his choice (the

second was never made). Connery plays Detective Sergeant johnson,

ajaded lawman who kills a suspected paedophile. In long takes and

wide/close montages, johnson reveals a Marnie-like secret: he too has

paedophiliac feelings. This time the law is right - and Connery's

character's moral imperative is not to challenge it but to admit to

his profound inability to live up to its demands.