He had also immersed himself in Stanislavsky, Shaw, Ibsen and

Tolstoy - and while these are writers any half-way serious actor must

address, his hunger for intellectual self-improvement took him as far

as james joyce and Finnegans Wake. (Didn't he find it impossible?

"No, no, I loved it, because it's marvellous language and because the

most erudite scholars have the same problems with it.") A photograph

taken in 1964 shows Connery standing on a pier, wearing only sky-blue

shorts. In his right hand, at head height, he holds an unidentifiable

open book. He reads it. This would be just another of those sexy

movie-mag pictures in which bodily display is made less outré

by a little outdoor action, until you recall all the books, all the

serious television plays. If it celebrates the corporeality which

struck others from the outset, it also signals his true inferiority.

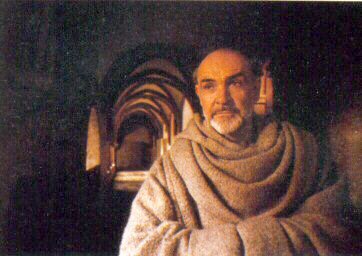

The mid-80s would see his rebirth as a significant marquee draw.

Since then, all his best roles have been booklovers, from William of

Baskerville, the monk detective using reason to solve a murder

mystery in The Name of the Rose (1986) , to Mason in The Rock, with his

book-lined cell - Mason, trained by British Intelligence, would

"rather be a poet". (In 1966 he had played the frustrated poet Samson

Shillitoe in A Fine Madness, a character so obsessed by books and

writing that writers' block drives him into mis-anthropic rage.) Then

there's one of his best performances, a role moving from the world of

thinking into the world of action: in Indianajones and the Last

Crusade (1989), he's Indy's dad, Professor Henry jones, a bookish

eccentric who has apparently lived his whole life in a library yet

can - in a funny, pivotal scene - down an attacking aeroplane, in a

stunt inspired by Charlemagne.

, to Mason in The Rock, with his

book-lined cell - Mason, trained by British Intelligence, would

"rather be a poet". (In 1966 he had played the frustrated poet Samson

Shillitoe in A Fine Madness, a character so obsessed by books and

writing that writers' block drives him into mis-anthropic rage.) Then

there's one of his best performances, a role moving from the world of

thinking into the world of action: in Indianajones and the Last

Crusade (1989), he's Indy's dad, Professor Henry jones, a bookish

eccentric who has apparently lived his whole life in a library yet

can - in a funny, pivotal scene - down an attacking aeroplane, in a

stunt inspired by Charlemagne.

This bibliophilia is all the more intriguing when we learn that it

has sometimes been emphasised in the scripts - or inserted into them

- at Connery's behest. Professor Henry jones was originally

introduced on page 70 of the screenplay - yet the way the film is

made, his entry comes somewhere around page 20. On The Rock, as

executive producer, Connery hired Ian LeFrenais and Dick Clements to

beef up his characters sation. "Yeah, I put those things in," he

says. "The books counterpoint what you are in the film." Is there a

link between the booklover and the rebel? The actor taught himself.

He likes other self-made people. Together, these attributes give us

the gospel according to Connery: people who have talent should not be

held back by social inequalities; and conversely, people should not

succeed simply because they are born into privi-lege. Meritocracy, in

a word, is the structuring principle behind his best films. (It's

also what the Scottish International Educational Trust, a charity he

co-founded, is about: in 1971, he donated his salary from Diamonds

Are Forever - at $1.25 million the highest then earned - to the

charity, which helps bright young Scots without resources to fund

their learning.)

So here I am, at home on my sofa - and Sean Connery is here too.

I'm interviewing him for a television programme (Scene By Scene,

based on the Edinburgh Film Festival's events of the same name).

Three cameras will run as we watch key scenes from his movies, with a

handset to freeze or slo-mo. I will grill him on what we're watching.

His face, besides being handsome, is very interesting. His

eyebrows are unusually arched, like facial quotation marks, adding

irony to his expression. His mouth is very wide, the opposite of

primness, and is emphasised by his post-Bond moustache. He's always

had a vertical line on either side of his mouth, which somehow

brack-ets it from his face. He has never really looked boyish, and

despite being just 12 and seven years older respectively, has played

the fathers of both Harrison Ford and Dustin Hoffman.

We are drinking wine and watching Dr. No. When the moment on the

beach arrives, Connery turns to me and says, "Ah, Ursula. I still see

her when I'm in Rome. She's still beautiful."

copyright: Sight and sound magazine, taken

from the may '97 issue

, to Mason in The Rock, with his

book-lined cell - Mason, trained by British Intelligence, would

"rather be a poet". (In 1966 he had played the frustrated poet Samson

Shillitoe in A Fine Madness, a character so obsessed by books and

writing that writers' block drives him into mis-anthropic rage.) Then

there's one of his best performances, a role moving from the world of

thinking into the world of action: in Indianajones and the Last

Crusade (1989), he's Indy's dad, Professor Henry jones, a bookish

eccentric who has apparently lived his whole life in a library yet

can - in a funny, pivotal scene - down an attacking aeroplane, in a

stunt inspired by Charlemagne.

, to Mason in The Rock, with his

book-lined cell - Mason, trained by British Intelligence, would

"rather be a poet". (In 1966 he had played the frustrated poet Samson

Shillitoe in A Fine Madness, a character so obsessed by books and

writing that writers' block drives him into mis-anthropic rage.) Then

there's one of his best performances, a role moving from the world of

thinking into the world of action: in Indianajones and the Last

Crusade (1989), he's Indy's dad, Professor Henry jones, a bookish

eccentric who has apparently lived his whole life in a library yet

can - in a funny, pivotal scene - down an attacking aeroplane, in a

stunt inspired by Charlemagne.